As a young girl, Caterina Sforza dreamed of great deeds that she would be a part of as a member of the illustrious Sforza family of Milan. Born in 1463, Caterina was the daughter out of wedlock of a beautiful Milanese noblewoman and Galeazzo Maria Sforza, who became Duke of Milan upon the death of his father in 1466. As duke, Galeazzo ordered that his daughter be brought into the castle, Porta Giovia, where he lived with his new wife, and that she be raised like any legitimate member of the Sforza family. His wife, Caterina’s stepmother, treated her as one of her own. The girl was to have the finest education. The man who had served as Galeazzo’s tutor, the famous humanist Francesco Filelfo, would now serve as Caterina’s tutor. He taught her Latin, Greek, philosophy, the sciences, and even military history.

Often alone, Caterina would wander almost daily into the vast castle library, one of the largest in Europe. She had her favorite books that she would read over and over. One of these was a history of the Sforza family, written by Filelfo himself in the style of Homer. There, in this enormous volume with its elaborate illustrations, she would read about the remarkable rise to power of the Sforza family, from condottiere (captains in mercenary armies) to ruling the duchy of Milan itself. The Sforzas were renowned for their cleverness and bravery in battle. Along with this, she loved to read books that recounted the chivalric tales of real-life knights in armor, and the stories of great leaders in the past; among these, one of her favorites was Illustrious Women by Boccaccio, which related the deeds of the most celebrated women in history. And as she whiled away her time in the library, all of these books converging in her mind, she would daydream about the future glory of the family, somehow herself in the midst of it all. And at the center of these fantasies was the image of her father, a man who to her was as great and legendary as anyone she had read about.

Although the encounters with her father were often brief, to Caterina they were intense. He treated her as an equal, marveling at her intelligence and encouraging her in her studies. From early on, she identified with her father—experiencing his traumas and triumphs as if they were her own. As were all the Sforza children, girls included, Caterina was taught sword fighting and underwent rigorous physical training. As part of this side of her education, she would go on hunting expeditions with the family in the nearby woods of Pavia. She was trained to hunt and kill wild boars, stags, and other animals. On these excursions she would watch her father with awe. He was a superior horseman, riding with such impetuosity, as if nothing could harm him. In the hunt, taking on the largest animals, he showed no signs of fear. At court, he was the consummate diplomat yet always maintained the upper hand. He confided in her his methods—think ahead, plot several moves in advance, always with the goal of seizing the initiative in any situation.

There was another side to her father, however, that deepened her identification with him. He loved spectacle; he was like an artist. She would never forget the time the family toured the region and visited Florence. They brought with them various theater troupes, the actors wearing outlandish costumes. They dined in the country inside the most beautifully colored tents. On the march, the brightly caparisoned horses and the accompanying soldiers—all decked in the Sforza colors, scarlet and white—would fill the landscape. It was a hypnotic and thrilling sight, all orchestrated by her father. He delighted in always wearing the latest in Milanese fashions, with his elaborate and bejeweled silk gowns. She came to share this interest, clothes and jewels becoming her passion. He might seem so virile in battle, but she would see him crying like a baby as he listened to his favorite choral music. He had an endless appetite for all aspects of life, and her love and admiration for him knew no bounds.

And so in 1473, when her father informed the ten-year-old Caterina of the marriage he had arranged for her, her only thought was to fulfill her duty as a Sforza and please her father. The man Galeazzo had chosen for her was Girolamo Riario, the thirty-year-old nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, a marriage that would forge a valuable alliance between Rome and Milan. As part of the arrangement, the pope purchased the city of Imola, in Romagna, which the Sforzas had taken decades before, christening the new couple the Count and Countess of Imola. Later the pope would add the nearby town of Forlì to their possessions, giving them control of a very strategically located part of northeastern Italy, just south of Venice.

In her initial encounters with him, Caterina’s husband seemed a most unpleasant man. He was moody, self-absorbed, and high-strung. He appeared interested in her only for sex and could not wait for her to come of age. Fortunately, he continued to live in Rome and she stayed in Milan. But a few years later some disgruntled noblemen in Milan murdered her beloved father, and the power of the Sforzas seemed in jeopardy. Her position as the marriage pawn solidifying the partnership with Rome was now more important than ever. She quickly installed herself in Rome. There she would have to play the exemplary wife and keep on the good side of her husband. But the more she saw of Girolamo, the less she respected him. He was a hothead, making enemies wherever he turned. She had not imagined that a man could be so weak, and compared with her father he failed by every measure.

She turned her attention to the pope. She worked hard to gain his favor and that of his courtiers. Caterina was now a beautiful young woman with blond hair, a novelty in Rome. She ordered the most elaborate gowns to be sent from Milan. She made sure to never be seen wearing the same outfit twice. If she sported a turban with a long veil, it suddenly became the latest craze. She reveled in the attention she received as the most fashionable woman in Rome, Botticelli using her as a model for some of his greatest paintings. Being so well read and cultivated, she was the delight of the artists and writers in town, and the Romans began to warm up to her.

Within a few years, however, everything unraveled. Her husband instigated a feud with one of the leading families in Italy, the Colonnas. Then in 1484 the pope suddenly died, and without his protection Caterina and her husband were in grave danger. The Colonnas were plotting their revenge. The Romans hated Girolamo. And it was almost a certainty that the new pope would be a friend of the Colonnas, in which case Caterina and her husband would lose everything, including the towns of Forlì and Imola. Considering the weak position of her own family in Milan, the situation began to look desperate.

Until a new pope was elected, Girolamo was still the captain of the papal armies, now stationed just outside Rome. For days Caterina watched her husband, who was paralyzed with fear and unable to make a decision. He dared not enter Rome, fearing battle with the Colonnas and their many allies in the crowded streets. He would wait it out, but with time their options seemed to narrow, and the news kept getting worse—mobs had sacked the palace they lived in; what few allies they had in Rome had now deserted them; the cardinals were congregating to elect the new pope.

It was August and the sweltering heat made Caterina—seven months pregnant with her fourth child—feel faint and continually nauseated. But as she contemplated the impending doom, the thought of her father began to occupy her mind; it was as if she could feel his spirit inhabiting her. Thinking as he would think about the predicament she faced, she felt a rush of excitement as she formulated an audacious plan. Without telling a soul of her intentions, in the dark of night she mounted a horse and snuck out of camp, riding as fast as she could to Rome.

As she had expected, in her condition no one recognized her and she was allowed to enter the city. She headed straight for the Castel Sant’Angelo, the most strategic point in Rome—just across the Tiber River from the city center and close to the Vatican. With its impregnable walls and its cannons that could be aimed at all parts of Rome, the person who controlled the castle controlled the city. Rome was in tumult, mobs filling the streets everywhere. The castle was still held by a lieutenant loyal to Girolamo. Identifying herself, Caterina was let into Sant’Angelo.

Once inside, in the name of her husband she took possession of the castle, throwing out the lieutenant, whom she did not trust. Sending word out through the castle to soldiers who swore loyalty to her, she managed to smuggle in more troops. With the cannons of Sant’Angelo now pointing at all roads leading to the Vatican, she made it impossible for the cardinals to meet in one location and elect the new pope. To make her threats real, she had her soldiers fire the cannons as a warning. She meant business. Her terms for surrendering the castle were simple—that all of the property of the Riarios be guaranteed to remain in their hands, including Forlì and Imola.

A few evenings after she had taken over Sant’Angelo, wearing some armor over her gown, she marched along the ramparts of the castle. It gave her a feeling of great power, so far above the city, looking down at the frantic men below, helpless to fight against her, a single woman hobbled by pregnancy. When an envoy of the cardinal who was organizing the conclave to elect the new pope was sent to negotiate with her and seemed reluctant to agree to her conditions of surrender, she shouted down from the ramparts, so all could hear, “So [the cardinal] wants a battle of wits with me, does he? What he doesn’t understand is that I have the brains of Duke Galeazzo and I am as brilliant as he!”

As she waited for their response, she knew she controlled the situation. Her only fear was that her husband would surrender and betray her, or that the August heat would make her too ill to wait it out. Finally, sensing her resolve, a group of cardinals came to the castle to negotiate, and they acceded to her demands. The following morning, as the drawbridge was lowered to let the countess leave the castle, she noticed an enormous crowd pushing close to her. Romans of all classes had come to catch a glimpse of the woman who had controlled Rome for eleven days. They had taken the countess for a rather frivolous young woman addicted to clothes, the pope’s little pet. Now they stared at her in astonishment—she was wearing one of her silk gowns, with a heavy sword dangling from a man’s belt, her pregnancy more than evident. They had never seen such a sight.

Their titles now secure, the count and countess moved to Forlì to rule their domain. With no more funds coming from the papacy, Girolamo’s main concern was how to get more money. And so he increased the taxes on his subjects, stirring up much discontent in the process. He quickly made enemies of the powerful Orsi family in the region. Fearing plots against his life, the count holed himself up in their palace. Slowly Caterina took over much of the day-to-day ruling of their realm. Thinking ahead, she installed a trusted ally as the new commander of the castle Ravaldino, which dominated the area. She did everything she could to ingratiate herself with the locals, but in a few short years her husband had done too much damage.

On April 14, 1488, a group of men, clad in armor and led by Ludovico Orsi, stormed into the palace and stabbed the count to death, throwing his body out the window and into the city square. The countess, dining with her family in a nearby room, heard the shouts and quickly shuffled her six children into a safer room in the palace’s tower. She bolted the door and from a window, under which several of her most trusted allies had gathered, she shouted instructions to them: they were to notify the Sforzas in Milan and her other allies in the region and urge them to send armies to rescue her; under no circumstances should the keeper of Ravaldino ever surrender the castle. Within minutes the assassins had broken into her room, taking her and her children captive.

Several days later, Ludovico Orsi and his fellow conspirator Giacomo del Ronche marched Caterina up to Ravaldino—she was to order the castle’s commander to surrender it to the assassins. As the commander she had installed, Tommaso Feo, looked down from the ramparts, Caterina seemed to fear for her life. Her voice breaking with emotion, she begged Feo to give up the fortress, but he refused.

As the two of them continued their dialogue, Ronche and Orsi sensed the countess and Feo were playing some sort of game, talking in code. Ronche had had enough of this. Pressing the sharp edge of his lance tight against her chest, he threatened to run her through unless she got Feo to surrender, and he gave her the sternest glare. Suddenly the countess’s expression changed. She leaned further into the blade, her face inches from Ronche, and with a voice dripping with disdain, she told him, “Oh, Giacomo del Ronche, don’t you try to frighten me. . . . You can hurt me, but you can’t scare me, because I am the daughter of a man who knew no fear. Do what you want: you have killed my lord, you can certainly kill me. After all, I’m just a woman!” Confounded by her words and demeanor, Ronche and Orsi decided they had to find other means to pressure her.

Several days later Feo communicated with the assassins that he would indeed hand over the fortress, but only if the countess would pay him his back wages and sign a letter absolving him of any guilt for such surrender. Once again, Orsi and Ronche led her to the castle and watched her closely as she seemed to negotiate with Feo. Finally Feo insisted that the countess enter the fortress to sign the document. He feared the assassins were trying to trick him and he insisted she enter alone. Once the letter was signed, he would do as he had promised.

The conspirators, feeling they had no choice, granted his request but gave the countess a brief time frame to conclude the business. For a fleeting moment, just as she disappeared over the drawbridge into Ravaldino, she turned with a sneer and gave the Italian equivalent of “the finger” to Ronche and Orsi. The entire drama of the past few days had been planned and staged by her and Feo, with whom she had communicated through various messengers. She knew that the Milanese had sent an army to rescue her and she only had to play for time. A few hours later Feo stood on the ramparts and yelled down that he was holding the countess hostage and that was that.

The enraged assassins had had enough. The next day they returned to the castle with her six children and called Caterina to the ramparts. With daggers and spears pointed at them in the most menacing fashion, and with the children wailing and begging for mercy, they ordered Caterina to surrender the fortress or they would kill them all. Surely they had already proven they were more than willing to shed blood. She might be fearless and the daughter of a Sforza, but no mother could possibly watch her children die before her eyes. Caterina wasted no time. She shouted down: “Do it then, you fools! I am already pregnant with another child by Count Riario and I have the means to make more!” at which she lifted her skirts, as if to emphasize her meaning.

Caterina had foreseen the maneuver with the children and had calculated that the assassins were weak and indecisive—they should have killed her and her family on that first day, amid the mayhem. Now they would not dare to kill them in cold blood: the assassins knew that the Sforzas, on their way to Forlì, would take terrible revenge on them if they ever did such a deed. And if she surrendered now, she and her children would all be imprisoned, and some poison would find its way into their food. She didn’t care what they thought of her as a mother. She had to keep stalling. To emphasize her resolve, after refusing to surrender, she had the cannons of the castle fire at the Orsi palace.

Ten days later a Milanese army arrived to rescue her, and the assassins scattered. The countess was quickly restored to power, the new pope himself confirming her rule as regent until her eldest son, Ottaviano, came of age. And as word of all that she had done—and what she had yelled down to the assassins from the ramparts of Ravaldino—spread throughout Italy, the legend of Caterina Sforza, the beautiful warrior countess of Forlì, began to take on a life of its own.

Within a year after the death of her husband, the countess had taken a lover, Giacomo Feo, the brother of the commander she had installed in Ravaldino. Giacomo was seven years younger than Caterina, and he was the polar opposite of Girolamo—handsome and virile, he had come from the lower classes, having served as the stable boy to the Riario family. Most important, he not only loved Caterina, he worshipped her and showered her with attention. The countess had spent her whole life mastering her emotions and subordinating her personal interests to practical matters. Suddenly feeling herself overwhelmed by Giacomo’s affection, she lost her habitual self-control and fell hopelessly in love.

She made Giacomo the new commander of Ravaldino. As he now had to live in the castle, she built a palace for herself inside it and soon barely left its confines. Giacomo was decidedly insecure about his status. Caterina had him knighted, and in a secret ceremony they married. To allay his self-doubts, she increasingly handed over to him governing powers of Forlì and Imola, and began to retire from public affairs. She ignored the warnings of courtiers and diplomats that Giacomo was out for himself and was in over his head. She did not listen to her sons, who feared Giacomo had plans to get rid of them. In her eyes, her husband could do no wrong. Then one day in 1495, as she and Giacomo left the castle for a picnic, a group of assassins surrounded her husband and killed him before her eyes.

Caught off guard by this action, Caterina reacted with fury. She rounded up the conspirators and had them executed and their families imprisoned. In the months after this, she fell into a deep depression, even contemplating suicide. What had happened to her over the past few years? How had she lost her way and given up her power? What had happened to her girlhood dreams and the spirit of her father that was her own? Something had clouded her mind. She turned to religion and she returned to ruling her realm. Slowly she recovered.

Then one day she received a visit from Giovanni de’ Medici, a thirtyyear-old member of the famous family and one of Florence’s leading businessmen. He had come to forge commercial ties between the cities. More than anyone else, he reminded her of her father. He was handsome, clever, extremely well read, and yet there was a softness to his character. Finally here was a man who was her equal in knowledge, power, and refinement. The admiration was mutual. Soon they were inseparable, and in 1498 they married, uniting two of the most illustrious families in Italy.

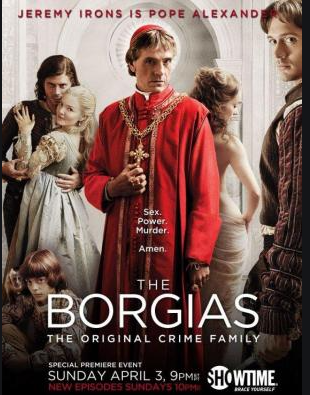

Now she could finally dream of creating a great regional power, but events beyond her control would spoil her plans. That same year Giovanni died from illness. And before she had time to grieve for him, she had to deal with the latest and most dangerous threat of all to her realm: The new pope, Alexander VI (formerly known as Roderigo Borgia), had his eye on Forlì. He wanted to extend the papal domains through conquest, his son Cesare Borgia serving as the commander of the papal forces. Forlì would be a key acquisition for the pope, and he began to maneuver to politically isolate Caterina from her allies.

To prepare for the imminent invasion, Caterina forged a new alliance with the Venetians and built an elaborate series of defenses within Ravaldino. The pope tried to pressure her to surrender her domain, making her all kinds of promises in return. She knew better than to trust a Borgia. But by the fall of 1499, it seemed that the end had finally come. The pope had allied himself with France, and Cesare Borgia had appeared in the region with an army of twelve thousand, fortified by the addition of two thousand experienced French soldiers. They quickly took Imola and easily entered the city of Forlì itself. All that remained was Ravaldino, which by late December was surrounded by Borgia’s troops.

On December 26, Cesare Borgia himself rode up to the castle on his white horse, dressed all in black—quite a sight. As Caterina looked down from the ramparts and contemplated the scene, she thought of her father. It was the anniversary of his assassination. He represented everything she valued, and she would not disappoint him. She was the most like him of all his children. As he would have done, she had thought ahead—her plan was to play for time until her remaining allies could come to her defense. She had cleverly fortified Ravaldino in a way that would allow her to keep retreating behind barricades if the walls were breached. In the end, they would have to take the castle from her by force, and she was more than prepared to die in defense of it, sword in hand.

As she listened to Borgia address her, it was clear he had come to flatter and flirt—everyone knew his reputation as a devilish seducer, and many in Italy thought Caterina had rather loose morals. She listened and smiled, occasionally reminding him of her past deeds and her reputation as a Sforza—if he wanted her to surrender, he would have to do better. He persisted in his courtship and asked to parley with her personally.

She appeared to finally succumb to his charm; she was a woman, after all. She ordered the drawbridge to be lowered and started walking toward him. He continued to press his case, and she gave him certain looks and smiles that indicated she was falling under his spell. Now only inches away, he reached for her arm, and she playfully withdrew it. They should discuss matters in the castle, she said with a coy expression, and began to walk back, inviting him to follow. As he stepped onto the drawbridge to catch up with her, it began to rise, and he leaped back to the other side just in time. Enraged and embarrassed by the trick she had tried to play, he swore revenge.

During the next few days he unleashed a torrent of cannon fire at the castle walls, finally opening a breach. Borgia’s troops flooded in, led by the more experienced French. It was now hand-to-hand combat, and at the front of her remaining troops was Caterina. The head of the French troops, Yves d’Allegre, stared at her in amazement as the beautiful countess—her ornamented cuirass over her dress—charged at his men from the front line, handling her sword deftly, without a trace of fear.

She and her men were about to withdraw further into the castle, hoping to prolong the battle for days, as she had planned, when one of her own soldiers grabbed her from behind and, his sword at her throat, marched her over to the other side. Borgia had put a price on her head, and the soldier had betrayed her for the reward. The siege was over, and Borgia himself took possession of his great prize. That night he raped her and kept her confined in his rooms, trying to make it seem to the world that the infamous warrior countess had willingly succumbed to his charms.

Even under duress she refused to sign away her domain, and so she was brought to Rome and soon thrown into the dreaded prison at Castel Sant’Angelo. For one long year, in a small and windowless cell, she endured her loneliness and the endless tortures devised by the Borgias. Her health deteriorated and she seemed destined to die in prison, defiant to the end, but the chivalric French captain Yves d’Allegre had fallen under her spell. He persisted in demanding, in the name of the French king, to have her freed, and he finally succeeded, getting her safe passage to Florence .

In retirement from public life, Caterina began to receive letters from men from all parts of Europe. Some had seen her over the years; most had only heard of her. They obsessed over her story, confessed their love, and begged for some memento, some relic to worship. One man who had caught a glimpse of her when she had first come to Rome wrote to her, “If I sleep, it seems that I am with you; if I eat, I leave my food and talk to you. . . . You are engraved in my heart.”

Weakened by her year in prison, the countess died in 1509.